Born in Fremont, Nebraska, Harold "Doc" Edgerton (1903-1990) began his graduate studies at MIT in 1926. He became a professor of electrical engineering at MIT in 1934. In 1966, he was named Institute Professor, MIT's highest honor.

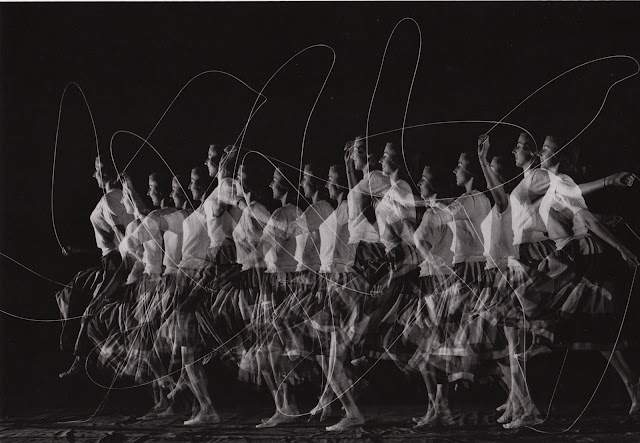

With his development of the electronic stroboscope, Edgerton set into motion a lifelong course of innovation centered on a single idea – making the invisible visible. An inveterate problem-solver, Edgerton succeeded in photographing phenomena that were too bright or too dim or moved too quickly or too slowly to be captured with traditional photography.

In the early days of his career, Edgerton's subjects were motors, running water and drops splashing, bats and hummingbirds in flight, golfers and footballers in motion, his children at play. By the time of his death at the age of 86, Edgerton had developed dozens of practical applications for stroboscopy, some that would influence the course of history.

The strides that Edgerton made in night aerial photography during World War II were instrumental to the success of the Normandy invasion and, for his contribution to the war effort, Doc was awarded the Medal of Freedom. During the Cold War, Edgerton and his partners at EG&G (Edgerton, Germeshausen, and Grier) made it possible to document nuclear explosions, an advance of incalculable scientific significance. In the last three decades of his life, Edgerton concentrated on sonar and underwater photography, illuminating the depths of the ocean for undersea explorers such as Jacques Cousteau, who dubbed his good friend "Papa Flash."

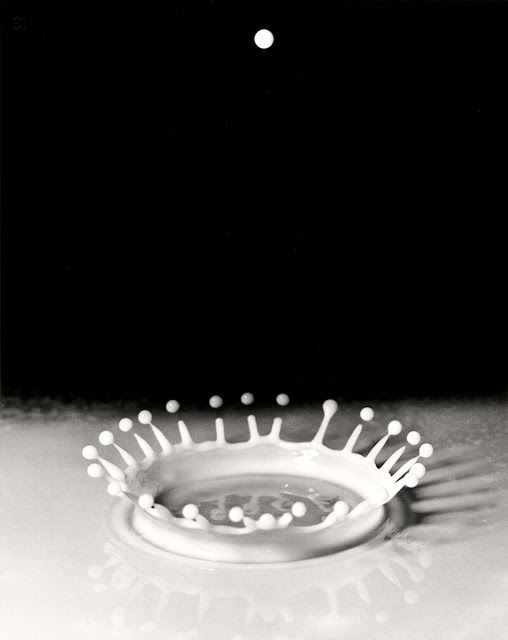

Doc's genius for revealing slices of time to the naked eye also engaged the public imagination. In part, this had to do with his astute choice of subject matter: Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland, the acrobats of the Moscow Circus, British tennis star Gussie Moran. But Doc's most famous study – and possibly his favorite – the milk-drop coronet, transcended its simple subject. The image, formed by the splash of a drop of milk, not only introduced the poetry of physics into popular culture, but forever altered the visual vocabulary of photography and science.

National Geographic used many of Edgerton's photographs as illustrations for its articles, and published a number of articles by Edgerton himself. Edgerton's photographs are exhibited in museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

With his development of the electronic stroboscope, Edgerton set into motion a lifelong course of innovation centered on a single idea – making the invisible visible. An inveterate problem-solver, Edgerton succeeded in photographing phenomena that were too bright or too dim or moved too quickly or too slowly to be captured with traditional photography.

In the early days of his career, Edgerton's subjects were motors, running water and drops splashing, bats and hummingbirds in flight, golfers and footballers in motion, his children at play. By the time of his death at the age of 86, Edgerton had developed dozens of practical applications for stroboscopy, some that would influence the course of history.

The strides that Edgerton made in night aerial photography during World War II were instrumental to the success of the Normandy invasion and, for his contribution to the war effort, Doc was awarded the Medal of Freedom. During the Cold War, Edgerton and his partners at EG&G (Edgerton, Germeshausen, and Grier) made it possible to document nuclear explosions, an advance of incalculable scientific significance. In the last three decades of his life, Edgerton concentrated on sonar and underwater photography, illuminating the depths of the ocean for undersea explorers such as Jacques Cousteau, who dubbed his good friend "Papa Flash."

Doc's genius for revealing slices of time to the naked eye also engaged the public imagination. In part, this had to do with his astute choice of subject matter: Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland, the acrobats of the Moscow Circus, British tennis star Gussie Moran. But Doc's most famous study – and possibly his favorite – the milk-drop coronet, transcended its simple subject. The image, formed by the splash of a drop of milk, not only introduced the poetry of physics into popular culture, but forever altered the visual vocabulary of photography and science.

National Geographic used many of Edgerton's photographs as illustrations for its articles, and published a number of articles by Edgerton himself. Edgerton's photographs are exhibited in museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

[via MIT]

Densmore Shute bends the Shaft, 1938. Edgerton was filming many notable PGA pros in this manner during the late 1930's.

Densmore Shute bends the Shaft, 1938. Edgerton was filming many notable PGA pros in this manner during the late 1930's.

Water from tap, 1939

Dynamite Cap, 1956

Atomic Bomb Explosion, before 1952

Atomic Bomb Explosion. Since each camera could record only one exposure on a sheet of film, banks of four to 10 cameras were set up to take sequences of photographs. The average exposure time was three millionths of a second. The cameras were last used at the Test Site in 1962.

Atomic Bomb Explosion. Since each camera could record only one exposure on a sheet of film, banks of four to 10 cameras were set up to take sequences of photographs. The average exposure time was three millionths of a second. The cameras were last used at the Test Site in 1962.

Pigeon release, 1965

Spooky the Owl, 1965

Milk Coronet,1957

Bullet through Apple, 1964

Although many consider Edgerton's work art, he said, “Don’t make me out to be an artist. I am an engineer. I am after the facts. Only the facts.”

"Cutting the Card," 1964, 1/1,000,000 exposure, .30 caliber bullet

Antique Gun Firing, 1936

Bullet through Jack of Hearts, 1960

Death of a Lightbulb, 1936

"Bullet Through Balloons," 1959 .22 caliber bullet.

"Puncturing a Balloon," 1977, 3/10,000,000 exposure, .22 caliber bullet

Bullet through rubber bands

Edgerton's notes show a measurement of 166 feet per second during Bobby's swing, which comes out to around 112 mph! Super fast for this era's heavier equipment!

In the lab/studio at MIT with golfer Bobby Jones

Densmore Shute bends the Shaft, 1938. Edgerton was filming many notable PGA pros in this manner during the late 1930's.

Densmore Shute bends the Shaft, 1938. Edgerton was filming many notable PGA pros in this manner during the late 1930's.Fly Fisherman

Golfer Bobby Jones, 1938

Dancer, 1952

Baton, 1953

Swirls and Eddies: Tennis ~ 1939

Pancho Gonzales, 1949

Football Kick, 1934

Boxer, 1940

Boxer, 1939

Jim Dotson Hits the Softball, 1938

Water Sprinkler, 1939

Cup of coffee on impact

Egg hits the fan with Edgerton

Dye Drop, 1960

Water Dropping into Water, 1978

Atomic Bomb Explosion, before 1952

Atomic Bomb Explosion

Atomic Bomb Explosion. Since each camera could record only one exposure on a sheet of film, banks of four to 10 cameras were set up to take sequences of photographs. The average exposure time was three millionths of a second. The cameras were last used at the Test Site in 1962.

Atomic Bomb Explosion. Since each camera could record only one exposure on a sheet of film, banks of four to 10 cameras were set up to take sequences of photographs. The average exposure time was three millionths of a second. The cameras were last used at the Test Site in 1962.Test Tube Breaking

Pigeon release, 1965

Spooky the Owl, 1965

Aerial flash photograph,1946, of the Pentagon taken by U.S. Army Air Force using equipment provided by Harold E. Edgerton.

Portrait of Edgerton at MIT

Edgerton with his flash equipment

Portrait of Harold Edgerton with his iconic image

Check out this funny and informative short "Quicker 'n a Wink"

by Harold Edgerton

Winner of the Academy Award for "Best One-Reel Live-Action Short Subject".

Very cool light experiments by Edgerton in this BBC documentary

.jpeg)

I am so pleased to see this post! I watched National Geographic's "Invisible World" way back in the day, and they featured "Doc" Edgerton's high speed photography, and the strobe light in the program. I was astounded!

ReplyDeleteIt was, of course, way before the Internet, digital photography, and, of course, photoshop!

A student of mine is an avid photography enthusiast (I teach English in Macau), and her project of time lapse photography jogged my time lapsed mind into thinking about this program, and "Doc". That's how I came across your site.

Thank you for putting this up, I think it is wonderful, educational, exciting, and a fitting tribute to not only Doc Edgerton, but also to photography, and posterity.

--James Paul Zaworski

I am so glad you enjoyed the post. Thanks for dropping by James!

Delete